Re-inventing the PMO

What could the PMO better? How can we increase the value of our PMO? What kind of PMO should we be?

PMOs tend to outlive their usefulness

A view that PMOs should not be permanent structures has gained ground recently. Tod Williamson, in his insightful book on “Filling Executive Gaps”, suggests that PMOs are perceived as essentially bureaucratic and they all tend to outlive their usefulness. The need to re-invent and re-align the PMO every few years to remain valuable has almost become a mantra in PMO circles.

John McIntyre at last year’s PMO conference talked about “How to survive that tricky third year“: and described how the PMO at Ticketmaster managed by doing more with less, deciding what to continue to provide and what to drop.

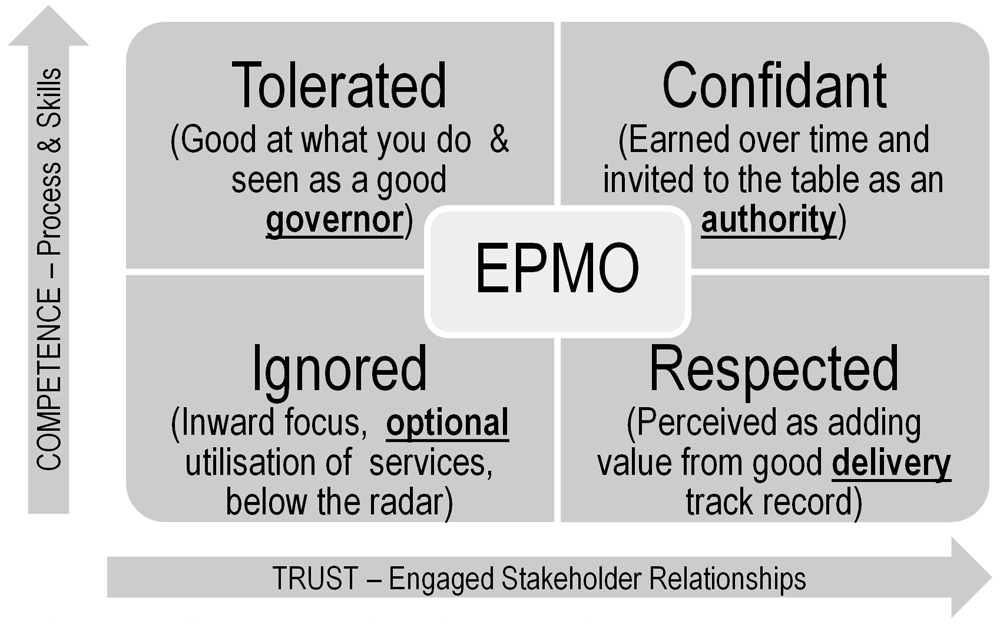

Michael Reynders of Mediclinic discussed the cycles of change that his PMO has gone through in its journey towards a ‘trusted partner’ of the board – an elusive target for many PMOs.

Michael Reynders of Mediclinic discussed the cycles of change that his PMO has gone through in its journey towards a ‘trusted partner’ of the board – an elusive target for many PMOs.

Re-inventing PMOs may be a necessity, but it is not easy. In one organization, the existing PMO had such a poor press with senior management that the path chosen was to create a competing PMO. This PMO, by providing exactly what the senior managers asked for, ensured the quick death of the existing PMO. This is not a route I suspect many of you would like to follow in your organization. So how to do you re-invent yourself – effectively and safely?

Here are four questions to get you started:

Current analysis: What do we do?

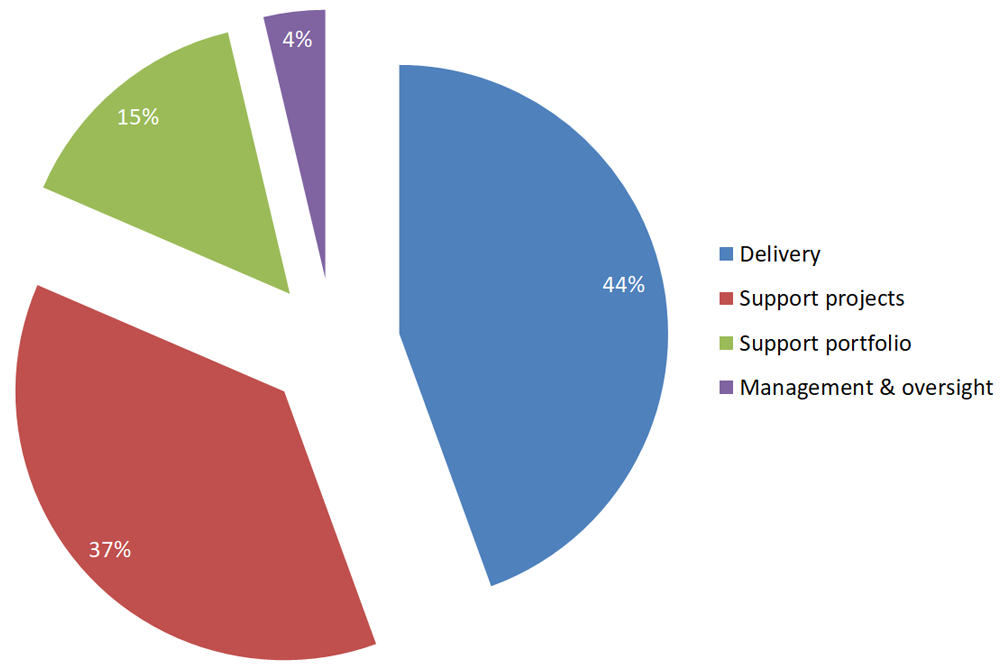

This question demands honesty and evidence. There is what you think you are doing, and there is what you and your team are really spending time on! The P3O functions list (you can find it at the back of the P3O manual) is a useful starting point. One perspective that has proved useful is to consider how much of the effort is delivery-related and how much is spent on infrastructure – or doing business with yourself. Is the split right? In the example shown, less than 60% of the effort is delivery-related. In discussions held with PMO managers on LinkedIn we found that a common target was 70% on delivery. Finding out what was actually achieved was rather harder to ascertain…

Current analysis: What should we be doing?

This second question is based on what we told our stakeholders we would deliver. Your charter is the right source for this. The chances are, if you are considering re-inventing yourself, then the charter has become less relevant, nevertheless it’s a good place to start. It will certainly highlight how good you have been at measuring your performance. Do you actually know if you are hitting the KPIs you promised? And can you answer all these questions: What should you stop doing? What should you be doing more of? And: What should you be doing better?

Future analysis: What are others doing?

If you are at the PMO conference then you have a really good opportunity to explore this – the lectures certainly, but even more so from discussions with other attendees. The PMI Pulse of the Profession report on PMOs suggests a few trends that are merging:

- Multiple department-focused PMOs being set up in corporates – how do you best exploit this and avoid duplication?

- Pressure is towards lean governance – and does Agile or agile-like approaches help

- Getting the right resources – the PMO supporting capacity and capability sourcing

- Creating a culture of project understanding across the organization

- Assessing the do-ability of projects as a key PMO capability to support portfolio management

Future analysis: What do our stakeholders want?

Lastly, and of course the most important question – What do our stakeholders want? But, who are your stakeholders? Who are the individuals and groups that care about the PMO now, and in the future? If it’s you, and only you, there is a problem looming!

The CITI stakeholder-centric model of PMOs identifies three groups of stakeholders:

The demand side – the senior managers and business units that want to understand how their money is being spent in projects, what they need to do to support the achievement of the project goals, and whether they are going to get value-for-money.

The demand side – the senior managers and business units that want to understand how their money is being spent in projects, what they need to do to support the achievement of the project goals, and whether they are going to get value-for-money.

The supply-side – the project managers and project specialists delivering project services to the organization who want to have information, administrative support, and sometimes guidance, particularly when competing for resources.

The third group is the PMO and its management. The table below suggests how the four types of PMOs become established. It makes for interesting reading.

The significance of the table is about how the PMO needs to engage – and the danger it faces if it becomes focused on how well it is carrying out the functions of the PMO.

Now you know who your stakeholders are, what is it that they want from the PMO? I wouldn’t bother with questionnaires and surveys or even some clever feedback process. Our experience is that these approaches are agenda-laden, politically-biased and do not reflect the real wants and needs of the stakeholders. The best way is to listen in the meetings you go to, what are the moans about, what factors get them interested and excited. Compile their desire-list from this grape-vine. Is your PMO delivering to this? If not, maybe the time has come to consider re-inventing your PMO.

Summarising statement

At the end of the last century PMOs were in demand – even fashionable. Since then there has been a decline, with only recently the beginning of a recovery. In part the recovery is a reflection of new trends in understanding how best to service the needs of the various program, portfolio and project communities, with PMOs, CMOs, VMOs and many other ‘flavors’.

To be valuable, and to provide the same level of service, it would seem PMOs must keep alive to the changes in interest and concerns of their stakeholders. It is not a set of functions, it is not a permanent structure; it is a capability to deliver support to delivery-focused activities.

Come and visit CITI to hear more about our case studies in this area, or contact me at: CWorsley@citi.co.uk