Going beyond Time, Cost, Quality in Project Management

So, how do you run a project as well as you can? The starting point is establishing the success conditions for the project. But, going beyond time cost quality these can be surprisingly hard to determine sometimes.

Years ago, when discussing project performance with CEOs of large corporations we would ask them to list the projects that had met their criteria of well-run projects. We were struck by the similarities between their responses. Projects that were mandated by legislation always featured and sometimes they were the only ones on the list. Why was this we wondered? What made them special? Well, the CEOs said, the objective was crystal clear; the end-dates were immovable as they were owned by external agencies; and obtaining and retaining the necessary project resources uncontested. Why then, we asked, did other projects continue to fail? To this question their heads would drop and they would mutter: “I’ve no idea, it’s a complete mystery!”.

Well in one way they were right. It is a complete mystery if they relied on the long-standing traditional ‘iron triangle‘ of project management–time, cost and quality, TCQ. This odd legacy just doesn’t deliver the right answer, and never did. It wasn’t until 1997, however, that commentators such as Shenhar and Bryde (amongst others) demolished this pernicious myth. Of course there are constraints such as budget and end-dates. These are crucial contributors to structuring a management activity as a project, but they have never been the way the success of a project is measured. Constraints and critical success factors (CSFs) combine to determine success, but there is always a hierarchy, some factors considered more important than others, and it is rare for time or cost constraints to be at the top. Look at the Sydney Opera House – late, late, late, and so overspent! The politicians were so incensed (and embarrassed) at the time by the project’s performance but today the structure is regarded as a triumph, is one of the world’s iconic buildings and put Sydney on the world’s stage. No doubting that this project is widely regarded as a success.

The dimensions of success

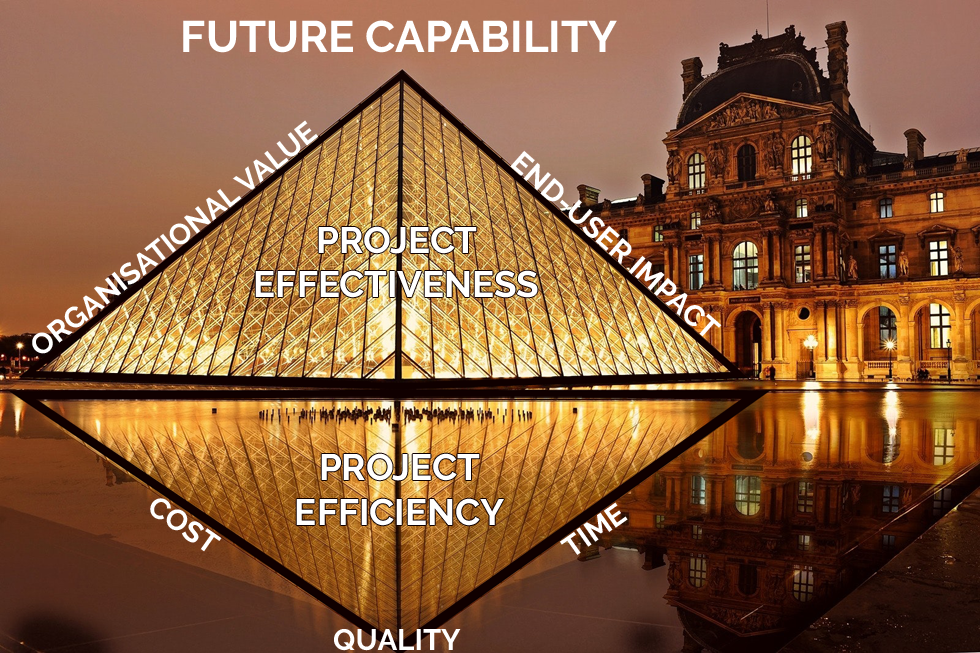

To better account for the facts–the way projects are determined as being a success or failure–Shenhar et al (2001) sum up the current view. There are, they say, four dimensions to satisfy:

- project efficiency

- impact on the customer

- direct business and organisational success

- preparing for the future

The first factor neatly bundles up the earlier ideas about traditional project management disciplines. The second and third reflect the growing realisation that unless the project returns something of recognised value, its performance in terms of delivering the outputs requested is worthless. The fourth focuses on what it is that the stakeholders have to bring to the party. It is their role to identify and develop the future capability of the organisation, to invest in organisational assets.

This ‘modern’ view of projects recognizes that success is not solely determined by the management actions of the project manager, but by how history passes judgment on the value of the project–an uncomfortable situation for some project managers.

Effect of the passage of time on project success factors

Figure 1 illustrates how the project success factors change with time, reflecting the changing mix of stakeholders who are making the judgments. The influence and interest of the role-based stakeholders–stakeholders who are involved in the local governance of the project–wanes. The agenda-based stakeholders–stakeholders who have an emotional or specific agenda associated with the project–become more significant. For more information on types of stakeholders, see Stakeholder-led project management (Worsley, 2016).

Given the inevitability of this evolution of stakeholders, projects must be planned to take into account not only the near-term success factors but also the longer term goals.

When doing it right is not enough

So how do you go about developing a project plan that delivers success when time, cost, and quality constraints are not the focus? Is there a set process?

The answers are: there is a process; it varies, and the determining factors are in the hierarchy of the project’s CSFs constraints. The planning process, the sequence of steps, and the models differ, and the choice is based, not on the content of the project, but on the conditions of success.

We have for many years been struck by the declining level of expertise and understanding of the role and value of planning in projects. Confusion about what and how to plan is exacerbated by what seems to be a recent deliberate conflation of planning with scheduling; tools that produce Gantt charts being called planning tools, and Agilists claiming there is no need to structure the future – all you need to do is ‘do it’.

To address this worrying lack of discipline, we have analysed the eight commonest project planning problems: projects where the conditions of success require that one factor above all others must be satisfied. There is no single approach to planning a project, but for a given set of circumstances, there is a best one, and the planning sequence is modified to ensure the project delivers to its success criteria. In a book published in February 2019 called Adaptive Project Planning (Worsley & Worsley 2019) we show how planning decisions alter depending on the project context. It discusses how resource-constrained planning differs from end-date schedule planning. It looks at what is different between cost-constrained plans and time boxing. It explores why you must plan when using Agile approaches, and how to plan for innovation.

With more and more businesses using projects to achieve their goals, this shift in emphasis on what makes a project successful; means that project managers can no longer safely use internal technical planning approaches. Having the right impact, creating value, realising sustainable benefits for the organisation means paying attention to factors that are far removed from just making allocation of resources to tasks, a shift of focus away from the delivery of outputs to delivering outcomes. These must always be defined by a combination of CSFs and constraints.

From iron triangle to golden pyramid

Given this new alignment of management attention to project success criteria rather than project execution–the real critical success factors sit on top of the iron triangle and are established by the consumers of the project. We are not advocating abandoning the iron triangle, but it takes its rightful place in this model as subservient to the delivery of value to the key stakeholders.

It should be clear that it is during the planning stage that these concerns need to be surfaced and we get there by asking these questions:

What does success look like? A surprising difficult question to answer for some sponsors– but persevere–because if they don’t know, it is unlikely you will come up with the right answer.

How do I know I’ve completed the project? Stopping the project just because you’ve reached the end-date is rarely a successful ploy, so how do you know when to stop? This is fundamental planning information.

How will the project be measured / judged? So basic, and yet so often overlooked. People tend to respond to what is being measured–it’s natural. Let it be known the number of smiles you make will be counted–and the number of smiles goes up. As the say in The Game of Thrones, “It is known!”

Success factors for a project set out those things that we must focus on in our planning and delivery. Critical success factors are, as their name implies, not important – they are critical! Should they not be achieved, the project will be seen to have failed. Similar to constraints, success factors are defined and owned by the project client, and the project must be planned and delivered to ensure their achievement, but they are often much more difficult to tease out from the stakeholders.

Clients will tell you that the budget is fixed; or the end-date. But, pay close attention to the actual decisions made. It quickly becomes clear that other factors–the real success factors are the ones that dictate the decisions, and their reactions of disappointment or delight.

A case that demonstrates this well is the Scottish Parliament building. Funded by public money and with a widely publicised end-date, when it came to making choices the stakeholders were much more interested in creating a prestige building with high aesthetic values and spring water flushing the toilets, than staying within budget or finishing on schedule. This might explain why it was delivered three years late–twice the original three-year estimate. It was 1,000% over budget–the original estimate was between £10m-£40m, and yet the actual cost was £414m. No iron triangle here!

The need to plan is paramount, and planning for success is the only sensible approach. In a companion book, The Lost Art of Planning Projects (Worsley & Worsley 2019) published in February 2019, we look at purposeful project planning and how to go about it in situations where the project is stand alone, is part of a portfolio, or is in a programme. In each case the focus changes but the intent remains the same: plan to win.

This article was written by Christopher Worsley, CEO of CITI Limited – and first published by Project Magazine in the Spring 2019 Edition.